Podcast – Ep.4 Andrew Steer, President & CEO of Bezos Earth Fund

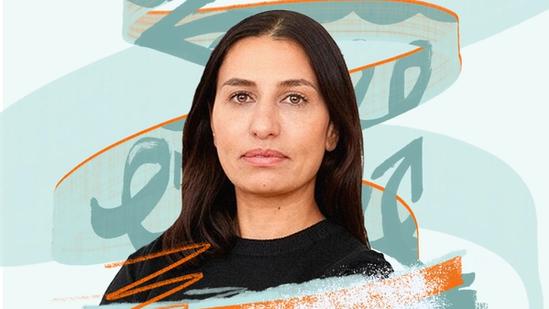

At COP29, Bahare Haghshenas, EQT's Global Head of Sustainable Transformation spoke with Andrew Steer, President & CEO of Bezos Earth Fund. Scroll to the bottom of this article to watch the full episode.

Bahare Haghshenas: Sir Andrew, it is a great pleasure to have you with us today.

Sir Andrew Steer: It’s a pleasure to be with you.

Bahare Haghshenas: How has your COP been so far?

Sir Andrew Steer: Well, I think we thought this was going to be a less buzzy COP. And actually, it’s full to the brim with interesting things going on. Obviously, negotiations are difficult, but most people are here to do things outside of the negotiations: doing all kinds of interesting deals, sharing ideas, and best practices. So yeah, it’s pretty good.

Bahare Haghshenas: And this is not your first COP, I guess?

Sir Andrew Steer: I think this is probably my 15th.

Bahare Haghshenas: Tell me about that journey. Is it moving in the right direction?

Sir Andrew Steer: Oh, definitely, definitely, yes. I mean, it’s always sort of two steps forward, one step back. But if we look at the Paris deal, it’s easy to say, “My goodness me, we’re losing the battle against climate change, so the Paris deal has failed.” But it’s important to remember that before the Paris deal, we were heading towards a world of temperatures rising by 4-4.5°c, which would be catastrophic. And we’re now heading towards a world of 2.5-3°c. That is still terrible, but there’s rarely been, you know, eight to nine years of progress as great as what we’ve seen.

And, of course, when the Paris deal was set up, it wasn’t supposed to solve it once and for all. It was set up in a very clever way. The world was not ready politically for a textbook solution. And so it had to be voluntary. And nobody whounderstood anything expected those first commitments, the so-called NDCs from countries, to be solving the problem.

The idea was that you have to raise your level of ambition every five years. The hypothesis was that costs would come down for green technologies, that the problems of climate change would become more evident, and that citizens would be willing to urge their governments to act.

And in a way, there’s been ups and downs, but it’s sort of heading in that direction. Now, we still are in a very, very serious situation. So, I’m by no means saying the problem is solved, but we still can be hopeful.

Bahare Haghshenas: Share with us that hope.

Sir Andrew Steer: If you look at the numbers, we are failing. Carbon emissions and greenhouse gas emissions are actually still rising, and they need to fall by 40 percent by 2030. So that’s going to be almost impossible, it sounds like.

The good news is something called exponential change. The future cannot be predicted by trends from the past. There’s a saying that says, “Things will always take much longer to happen than you expected, and then they will happen quicker than you could have ever dreamed.”

And that is what happens: technology, adoption and new policies don’t come in a linear fashion. The future won’t be driven by straight lines or even smooth curves but by what, in America, they call hockey sticks. You know, you go along, and then you jump up.

So, the name of the game for us and everybody who cares is how do we identify those potential hockey sticks and remove barriers that are preventing them from happening?

“If you look at the numbers, we are failing. Carbon emissions and greenhouse gas emissions are actually still rising, and they need to fall by 40 percent by 2030.”

Bahare Haghshenas: If we look at this COP, which is called the Finance COP, what are the hockey sticks that we need to nail really well before the end of next week?

Sir Andrew Steer: The reason that finance matters this year, in particular, is because this is the year that countries need to come up with their next and more ambitious so-called NDC, which is their national plan.

And countries in the emerging and developing world are understandably saying, “Well, we’d like to be ambitious, but you’ve got to help us out a bit. You know, we’re pretty indebted. Our fiscal situation is not good.”

And so it’s very, very important for substantive and political reasons that players here are able to lay out a really ambitious financing story. And it doesn’t all have to be grants by any means. I mean, we, as a philanthropy, provide grants, but actually, overwhelmingly, the finance will come from the private sector. But the private sector needs to be helped.

So, if you are a donor, that is, you give grant money, maybe you should focus on: “How do I de-risk the private sector? How do I provide guarantees? How do I take first losses?”, and so on.

So, there’s a lot of innovation here at the moment.

Bahare Haghshenas: Going back to the comment you had about two days ago, we started to discuss carbon markets. Do you have any insights? Do you know where we are going with that? Because that’s an important instrument, especially for investors.

Sir Andrew Steer: Yes. I mean, there’s Article 6 in the Paris deal, which we’ve never really landed. And we still haven’t landed it, but at least now there is agreement on the principles.And it’s really important that this happens, not because we want to allow countries to take their foot off the pedal for their own decarbonization, but because there are some things that are very hard to do and will take until the next decade.

For example, if you want to totally decarbonize airline traffic, you won’t be able to do it this decade. However, you can start by doing all the research, and gradually, sustainable aviation fuel will become a bigger percentage of airline traffic.

But in the meantime, you want to be compensating for all of the emissions that come. And that’s where Article 6 can play a helpful role.

Of course, all the corporations are nested under the national commitments. We’re working a lot on voluntary carbon markets because we believe that there are companies that are working very, very well to reduce Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions.

They’re trying their hardest on Scope 3, but Scope 3 is very hard. And so the standard-setting body called VCMI (the Voluntary Carbon Markets Initiative) has come up with a rule that says if you’re doing Scope 1 and 2 and if you’re doing your very best on Scope 3, then maybe 25 percent of your Scope 3 you should legitimately be able to compensate.

For example, using it to close coal plants in Indonesia would be really cool. However, implementing the transitions in these countries is currently very, very expensive.

Bahare Haghshenas: And where do you think we will land with that conversation by the end of next week?

Sir Andrew Steer: I don’t know how they’re going to.

Bahare Haghshenas: What do you hope for?

Sir Andrew Steer: Progress, but more broadly on the finance agenda. In Copenhagen in 2009, we came up with this $100bn figure, and it took until 2022 to reach it. They were supposed to reach it in 2020. They also diluted the definition of it quite a bit in the process.

So well done, but now it needs to be for the next period; thereneeds to be a commitment. And ideally, one wouldn’t just have one number because, quite frankly, the one number is just a mix of things.

It includes grants from bilateral aid agencies, concessional loans, all the money from the World Bank and regional banks, and private sector money catalyzed by that. It’s sort of apples, pears,and socks all thrown in together.

What would be smarter would be to say, “Okay, here’s what we need in concessional money, and here’s the private sector money that needs to be brought to the table.” And we need to have a much richer notion of how we bring these different sources of money together.

Bahare Haghshenas: I would like to learn more about the Bezos Earth Fund. You have some guiding principles that ensure that you make the greatest impact when you invest. Tell me about them.

Sir Andrew Steer: Well, we hope they ensure that, yes. We are willing to take risks. You know, as a philanthropy, we have to ask ourselves, “What can we do that others can’t?” We can move quickly, take risks, invest small amounts quickly to see if they work, and then scale them up, so to speak. So, we have much more flexibility than many other sources of money.

We are privileged, thanks to the incredible generosity of Jeff Bezos, who put $10bn on the table and said, “Let’s allocate this money during this decade” That’s a huge privilege. While $10bn sounds like a lot – it is to me and probably to you – it’s actually a small amount compared to the trillions needed. So, you really have to think strategically about how to maximize its impact.

That’s why we run something together with WRI [World Resources Institute] called the System Change Lab. It looks at 50 transitions that are required. Fifty sounds like a lot, but if you start thinking about it very quickly, they mount up. You’ve got to shift diets, get rid of the internal combustion engine, improve energy efficiency…you name it.

Each is pretty chunky, so every year, we review their progress and ask, “How close are they to a tipping point, beyond which change becomes irresistible and unstoppable?” Our job is to remove barriers to that tipping point.

Bahare Haghshenas: I heard you just launched a project around AI and nature. Tell me about that.

Sir Andrew Steer: We just launched a $100m competitive program. We picked a few themes: alternative proteins, managing the electric grid, and monitoring and addressing nature and biodiversity.

We recently received a couple of thousand applications and are sifting through them. Soon, we’ll announce small grants to about 30 of them and much larger grants to around 15 of them.

Bahare Haghshenas: If you look at your impressive career, you’ve done so many different things in different industries and sectors. if you were to advise investors, where should they look if they want to invest in climate?

Sir Andrew Steer: Well, I think what you’re doing at your own investment company is pretty clever, actually. I think you’re identifying some technologies that, quite frankly, are going to grow and grow, and infrastructure as well.

For example, battery storage. The arc of history is moving towards certain technologies, no question about it. It might go slower than we need, but it’s heading in that direction.

So, I would urge investors to understandably focus on what they need in the short term but also to please focus on the long term. For example, 50 years from now, we’re going to have to eatquite differently.

Currently, meat consumption is rising very rapidly and is expected to increase by 60 percent by 2050 under current trends. If that happens, and remember livestock accounts for 80 percentof all agricultural land, half of all usable land, and 15 percent of all carbon emissions, then we will absolutely fail on climate change.

We have to dramatically shift that curve, which will require alternative proteins. But if we don’t, we’ll also lose nature – like the Amazon rainforest – because that’s where the pressure is: cattle farming and the soy for chickens and pigs.

I would urge investors to keep one eye on short- and medium-term gains, but please keep the other eye on the long term.

Bahare Haghshenas: And I’d like to return to your earlier point about hope. You’ve been on this journey for many years. Are you still hopeful?

Sir Andrew Steer: Yes, I’m definitely still hopeful. Obviously, the Paris deal aimed for well below two degrees. Since then, we’ve agreed on 1.5 degrees. Quite frankly, we’re probably going to blow through 1.5 degrees. But we can stay well below two degrees, and then we can come back down to 1.5 or below.

There are technologies that will enable us to take carbon out of the atmosphere. It’s going to be unbelievably challenging to do that.

What we need are leaders, including in the financial and investment sectors, who say, “For such a time as this, this is why I went into this field.” To wake up on a Monday morning and think, “I am part of a cadre of change-drivers.”

It’s thrilling. And hopefully, our grandchildren will look back and say, “Wow, what we did back then made a difference.”

We just had a big plenary session today, which I was asked to chair. We brought together people from the private sector, philanthropy, and investment.

The exam question for all of them was, “It’s 2050 and we’ve succeeded. What would you have done in 2024 and 2025 to deliver that success?”

We had an incredible group of participants, the president of AIIB, Alok Sharma, and many others. There were about 700 people in the room. At the beginning, I asked everyone to close their eyes and imagine it’s 2050. I said, “What does the world look like? How do we live? How do we travel to work? What do we eat? What are our education systems like? Think about that, and then ask yourself what it would take to get there.”

It was incredibly inspiring, and that’s what we have to do. This is the most exciting economic and social transition ever.

And it doesn’t mean we have to sacrifice prosperity for even a moment. Done right, we will be richer, healthier, breathe cleaner air, have nicer parks, and eat better food.

Bahare Haghshenas: That’s an amazing hope to put on the table. If you had magic, what is the one thing you would change to really accelerate progress?

Sir Andrew Steer: One single thing: a mindset change.

If leaders everywhere could wake up each day and think, “How can I be part of this amazing adventure to make a difference for the planet?” rather than focusing solely on personal success, it would transform everything.

If someone else gets the credit for something and I’ve been helpful to them, that should be just fine. I know it sounds a bit spiritual, but there is a kind of spiritual element here.

If we approach this with the idea that we were called to this planet to be part of something extraordinary, we can truly change the trajectory of our future.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview reflect those of the participants and do not necessarily represent the official policies, strategies, or commitments of EQT AB or its affiliates.

ThinQ is the must-bookmark publication for the thinking investor.